The Great Famine of 1315-22

A comprehensive overview of some of the causes and effects of the fourteenth-century famine in the British Isles.

Enter Blog

Public History in a digital world: Digital Project

Mallory McCallum

User Guide

This website is entirely interactive. All images and in-text footnote citations are "clickable" and all lead directly to the citation page so that you can learn more about the content or where the information is from. Each subsection of this website has "Home" buttons that will direct you back to the main menu page. Additionally all boxes on the main menu page will relocate you to your desired subsection. I hope you enjoy this website!

Overview

Understanding the Great Famine

In the fourteenth century, a vast region of Europe endured extreme calamities. The first of which was a catastrophic famine. This famine began in 1315, and Europe, specifically Northern Europe, started to recover in 1322. The leading causes of the Great Famine included climatic issues and an agrarian crisis. Within the British Isles, the famine paved the way for many other crises that contributed significantly to the ongoing extremities. Following the vast devastation caused by the Great Famine, the British Isles continued to face further ruin with the onset of the bubonic plague, which added to the already catastrophic number of casualties. This blog aims to thoroughly examine the causes and effects that the Great Famine of 1315-1322 had on the British Isles, as well as provide an understanding of why this period was the beginning of what is now known as the “Dark Ages.”

Ineractive Timeline

Spread through Southern parts of England and Ireland and fully ravaged the British Isles by 1349.

With scarce food availability and fluctuating weather, livestock perished from pestilence, starvation, and weather.

Summer months of extreme precipitation followed by harsh winters which continued until 1322.

Or the "Medieval Warm Period." It ranged from 800-1300 and was caused by glacial withdrawal.

It lasted from the 13th to the 19th century which created unusually low year-round temperatures which was felt globally.

Wet conditions led to a disproportionally low harvest which was mostly unusable.

Rain began to recede, and harvests returned to yields comparable to before the famine.

- Poem on the Evil Times of Edward II, c. 1327

“Came there another sorrow that spread over all the land;

A winter that was stronger than a thousand that came before.

To bind all the many men in mourning and in care,

The Cattle died all forthwith, and made the land all bare, so fast,

Came never a wretch into England that made men more aghast.”

The Little Ice Age was a period of year-round global cooling which lasted from the thirteenth to the nineteenth century. It was preceded by an event known as “The Great Warming,” which was caused by increased solar irradiance. From field data based on ice core and tree ring samples, it is believed that the Little Ice Age was likely caused by decreased solar irradiance as well as changes in the thermohaline circulation (also called the Great Ocean Conveyor Belt). The “conveyor belt” brings warm water from the south, and when climatic changes (i.e., El Niño/Niña) occur, the Northern hemisphere is impacted by colder weather conditions. The Little Ice Age caused glacial advancement and unpredictable weather anomalies.

Contributing FACTORS

The Little Ice Age

Heavy Rainfall

In 1315, seemingly never-ending torrential rain began in Northern parts of Europe. The sudden onslaught of rain was unexpected as the previous century had seen a long period of drier weather. The unexpectedness of this downpour left people unprepared and ill-equipped. According to records from England and other European countries, there were one hundred successive days of rain in 1315. Hydroclimatic data show that the summer of 1315 was the wettest compared to other years. The sheer intensity of the rainfall led people to believe this was the first wave of the apocalypse and was compared to the biblical story of Noah and the Great Flood. The battering of rain that farm fields faced prevented the soil from adequately draining, making seeds float and not take root and becoming readily available to wild animals. The endless rain cycles and damage to crops directly ruined three consecutive harvests.

Effects of Crop Failure

"A dysentery-type illness, contracted on account of spoiled food emasculated nearly everyone, from which followed acute fever or throat ailment. And so men, poisoned from spoiled food, succumbed, as did beasts and cattle, fell down dead from poisonous rottenness of the grass. Nor does anyone remember so much dearth and famine to have prevailed in the past, nor so much mortality to have attended it.”

- An account of symptoms of food related deaths, likely caused by ergotism or ill-diet, from monk John of Trokelow's chronicles.

The extreme weather anomaly of intense rain caused by the Little Ice Age proved fatal to crops. The incessant downpour of rain caused a reduction in harvest yields in some regions of the British Isles of up to 70% compared to years prior to the Great Famine. This reduction in harvestable goods is made even worse when noted that in the years before 1315, harvests in the British Isles were already producing less yield, which caused a surge in the cost of victuals. Due to the dramatic weather, scarce wheat was salvageable during harvest season as seeds had rotted, and the hay had essentially drowned after being pestered by continued rain. According to a record documented in the second edition of John Aberth’s book From the Brink of the Apocalypse: Confronting Famine, War, Plague, and Death in the Later Middle Ages, in 1316, “little grain grew that year, nearly all of it having perished,” from the poor weather conditions. The Bolton Priory, located near the Scottish and English border, yielded crops compared to seeds sown less than a one-to-one ratio. While a reduction of harvestable goods and food scarcity was a concern, the Great Famine mortalities were also caused by the inability to eat appropriate nutrition as well as food-related illnesses. The wet weather preventing bountiful harvest was worrisome; however, what was even more distressing was the crops that were harvested as the precipitation created excellent conditions for the growth of plant diseases like ergot fungus. Ergot fungus grows ideally on damp grain that previously was impacted by extreme winters. Ergotism happens in people and animals alike when ingested orally. The impact of ergotism in the human body affects the central nervous systems or muscles and creates hallucinogenic symptoms. When affecting the muscles, it causes painful involuntary spasms, which prevent blood circulation into limbs, becoming gangrenous and fall off. In both forms of ergotism, excruciating death follows.

25

26

27

War with Scotland

In the late summer of 1311, Scottish supporters of Robert the Bruce (1274-1329) initiated the first of a long series of raids in the North of England. These raids were strategically planned their raids during harvest time and destroyed or burned all available crops in the counties of Cumbria, Durham, Northumberland, and York. The timed raids spread chaos to force King Edward II of England (1284-1327) to recognize Robert the Bruce as King of Scotland. Scottish raids lasted nearly every year of the famine, which only created more food scarcity and did not end until 1327. While the raids strongly impacted crop yields, they also targeted livestock to steal, specifically cattle and horses. However, Scottish raids were not only damaging to the English as troop movement and the herding of livestock over the border allowed for the spread of animal murrains. The spread of animal disease impacted Scotland, causing a mass decline in their livestock, further impacting the famine on Scottish soil. Robert the Bruce’s ambitions of becoming King were also shared by his brother Edward Bruce (1280-1318), who launched an invasion

of Ireland in the summer of 1315 with aspirations of becoming a King in his own right on the Emerald Isle. Further Scottish troop and cattle movement to Ireland allowed disease transmission to impact Irish livestock. The impact of the animal murrain and raids on Ireland was made worse with the onset of the famine in the country. The conflicts between the Scottish and Anglo-Irish in 1315 left no “corn nor crop” in its wake as it had all been destroyed, and thousands of livestock were killed. Supporters of Edward Bruce also faced internal famine, which resulted in mass food-related deaths.

England

In response to the famine in England, King Edward II attempted to import grain and give it to the counties most in need. In Berwick-upon-Tweed in Northumberland County, a shipping port was established to import grain as a means to combat weather and Scottish raid-induced famine. The flow of grain travelling from Dover to Berwick-upon-Tweed via the North Sea became subject to intense piracy; not only from Scots and other European countries but also by English pirates. Edward II also pleaded with noblemen to discourage grain hoarding, which caused markets to surge, and gently reminded nobles not to be “the cause of so great [of a] ruin and death among people… [for] having grain and refusing to sell it.” Parliament also made several attempts at stabilizing the rising cost of victuals by introducing “fixed” market pricing that would reflect the bountifulness of the harvests.

Scotland

Ongoing Scottish raids on England proved to have irreparable damages on both sides of the border. The transmission of animal murrains from the raids was especially catastrophic to the cattle. The cattle plague in Scotland devastated the Gaelic farming communities in the Highlands as they were reliant on livestock as not only a source of food but also used to carry out physically demanding work such as ploughing.

Ireland

In 1317, the cost of food in Dublin became so expensive that there was an influx of people who took to begging in order to provide support for their families, but still, many people perished. On top of the famine, between 1315-1318, Ireland was invaded by Edward Bruce, which contributed to excess loss of life. At the battle of Fochart in October 131, Edward Bruce met his end, which was celebrated country-wide. In the Annales of Connacht, it is stated that he was “the common ruin” of the Irish people, and there was no “better deed done than” his death. During Bruce’s time in Ireland, the country was heavily impacted by famine and unnecessary death.

Social Impact

Cannibalism

Reports of cannibalism were rampant during the Great Famine throughout Europe. In John of Trokelow’s chronicles, he indicated that people were eating untraditional animals and “other unclean things,” alluding to cannibalism. His chronicles also detail peasantry stealing children to be consumed. In Ireland, the Annals of Connacht parents began eating their children as a means to survive, and in England, Trokelow gives an eerily similar report. During the Scottish invasion of Ireland, it is claimed that both parties, having suffered from the famine, began consuming one another and, in some cases, exhumed bodies and scooped “out there skulls for food.”

Crime and Beggars

TIn Kent, from 1316-7, of the investigated crimes that were committed, 70% of them involved some form of stealing of livestock or food. During the famine, poor people suffered the greatest and resorted to thievery, rioting, and begging. One of the biggest problems caused by beggars was that they often swarmed cities and created an influx of illness in urban hubs.

Begging

This is prime space! Use it to elaborate on your attention-grabbing section title. Explain what this section is about, share some details, and give just the right amount of information to get the audience hooked.

Economy

The Great Famine had an immense impact on the economies of the British Isles. From the first year of the famine in 1315, there was a rise in the cost of grain to 40 shillings as compared to 5 shillings in 1313. During the height of the famine, the average cost of wheat was 40% higher than the decade previous. The massive crop failures of 1315-1317 caused many farmers to severely undermine year-round budget concerns, prompting a surge of land and home sales for people to make ends meet.

Crime

This is prime space! Use it to elaborate on your attention-grabbing section title. Explain what this section is about, share some details, and give just the right amount of information to get the audience hooked.

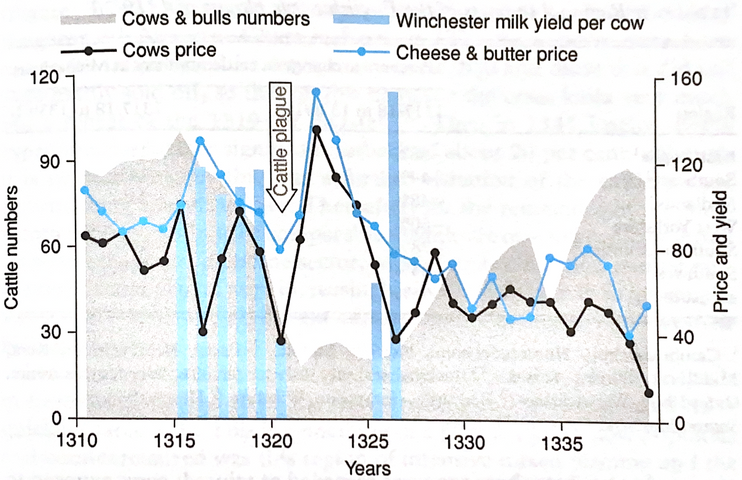

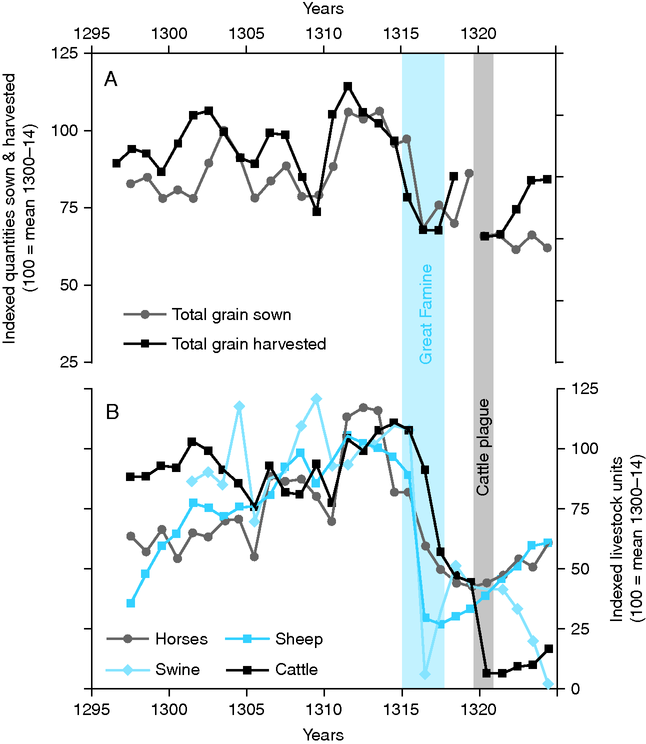

Impact on Livestock

The weather during the Great Famine became the greatest enemy of all livestock for many reasons. On top of weather, a factor that added to the mass animal mortality was humans. In Berwick-up-Tweed, Northumberland, people began boiling off the meat from recently deceased horses to eat in February of 1316. Berwick’s hardships with livestock were unnecessarily exaggerated by constant raids and theft of animals by the Scots. According to John of Trokelow’s chronicles, English people began commonly eating horses, dogs, cats, mice, and pigeon feces. On the Bolton Priory in West Yorkshire, the onset of the famine forced the slaughter of 94% of all the available pigs for human consumption in 1316. In the same year on the Bolton Priory, roughly two-thirds of their sheep succumbed to liverfluke. Weather was so dangerous to animals at this time because highly contagious diseases were formed due to the wet and cold conditions. Liverfluke ultimately affected around one-third of all sheep in England. The Great Cattle Plague that hit England, Scotland, and Wales, from 1319-20 created increased food scarcity because of the high mortality rate of rinderpest. In the Bolton Priory, rinderpest killed 84% of the cattle compared to the English national average of 56%. Scottish raids of English cattle introduced and spread rinderpest throughout Scotland. The animal murrains devastated the cattle-rearing-dominated communities of Wales and the Scottish Highlands. According to the Chronica Gentis Scotorum, nearly all livestock had been affected in Scotland. The Cattle Plague impacted Ireland most significantly in 1321 and lasted until 1326 and, from accounts, had a loss “of great proportions.”

English Regions | Percentage change in cattle numbers from 1317-1321 |

East Anglia | -28% |

Southeast | -44% |

Midlands | -48% |

West Yorkshire | -60% |

Southern Counties | -78% |

Southwest | -84% |

NATIONWIDE AVERAGE | -56% |

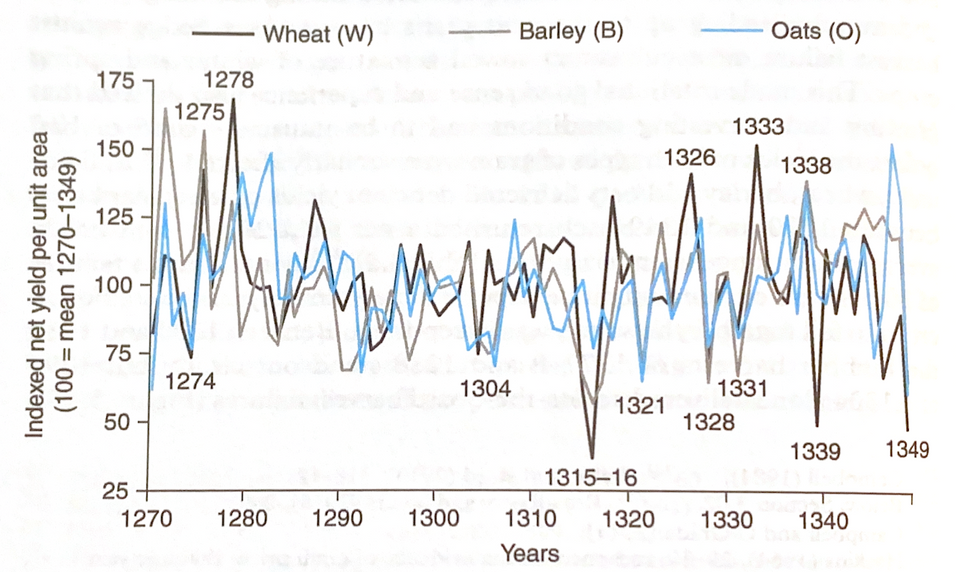

Change in Harvests

Aftermath

Despite the return of fruitful harvests in 1322, employment was still low, and the cost of seed continued to rise. National income continued to worsen as food prices soared amid farmers' wages reaching their lowest. During this time, the average cost of foodstuffs and other necessities doubled. The British Isles' economy did not fully recover to the pre-famine cost of living and harvest yields until right before the onset of the Black Plague in 1348.

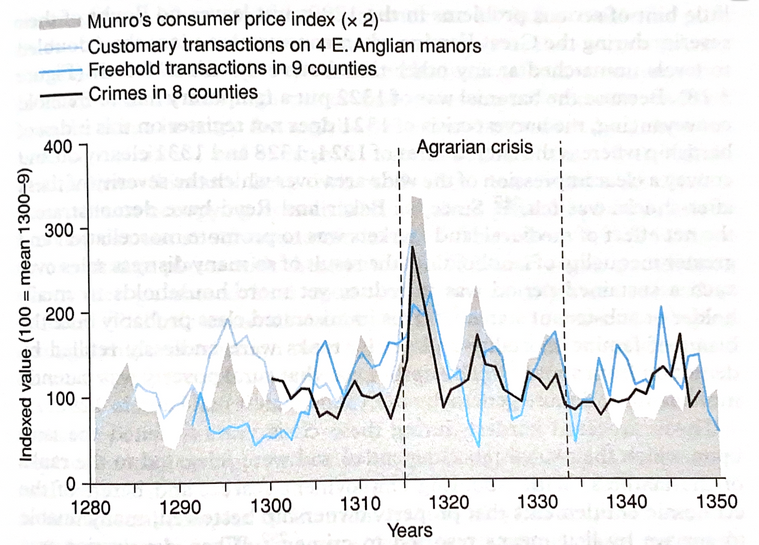

Trends and Changes Before, During, and After the Famine

Figure 3.26 from page 223 of Campbell's The Great Transition demonstrating the correlation between cattle plague and rising prices in England between 1310-1340.

Figure 3.18 from page 195 of Campbell's The Great Transition showing the changes in pricing, land transactions, and crime rates in England from 1280-1349.

Figure 3.23 from page 212 of Campbell's The Great Transition detailing the impact of the agrarian crisis of 1315 on the agricultural economy of the Bolton Priory in West Yorkshire.

Figure 3.15 from page 190 of Campbell's The Great Transition documenting English net grain yields per unit area from 1270-1349.

In England, the overall mortality rate from the famine was between 10-15%, with an additional 10-15% chance of death among peasantries. Halesowen in Worcestershire had one of the highest mortality rates during the famine. Despite the high mortality post-famine, marriage tax records indicate a massive surge in weddings from the 1320s-1340s, likely as a result hopeful reproduction of children in Halesowen. Across England, there was a rise in births after the famine, likely because of more food availability and regrowth. From a population survey comparison between 1086 and 1377, the population of England rose from two to three million people; while this growth is small, it is essential to note that during this time, there was famine, war, and epidemics.

The Black Plague

When the British Isles slowly began to recover from the disastrous famine of 1315-1322 in the mid-fourteenth century, they were soon struck by an even more devastating plague. The plague that struck the British Isles is scientifically called yersinia pestis, which takes three different forms. The most common form is the Bubonic form which produces pustules buboes. Compared to the 10-25% mortality rate of the Great Famine in England, the Black Plague had a mortality rate of 45-62.5%. The resurgence of birth rates that occurred in the 1320s-1340s had little impact in preventing mass loss during the plague as birth rates dropped between 32-64% across England. The plague coming nearly immediately after the Great Famine created a perfect storm of calamities which made this period so devastating and gives reason as to why this time is called the “Dark Ages.”

Click citations to take you back to the page they appear on!

Citations

As they Appear in Text, Image Citations are cited after in-text citation 100 and are cited in order of appearance.

- John Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse: Confronting Famine, War, Plague, and Death in the Later Middle Ages – Second Edition (London: Routledge, 2010), 16.

- Bruce M.S. Campbell, The Great Transition: Climate, Disease and Society in the Late-Medieval World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 205.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 10.

- Robert W. Strayer, and Eric W. Nelson, Ways of the World: A Brief Global History with Sources – Fourth Edition (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2019), 552.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 11.

- Ibid, 10.

- Campbell, The Great Transition, 221.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 23.

- Ibid, 81.

- Strayer, et al., Ways of the World, 552.

- Campbell, The Great Transition, 52.

- Ibid.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 13.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 10.

- “The Evil Times of Edward II 1327,” in From the Brink of the Apocalypse: Confronting Famine, War, Plague, and Death in the Later Middle Ages – Second Edition, ed. John Aberth (London: Routledge, 2010), 10.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 11.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 9.

- Seung H. Baek, Jason E. Smerdon, George-Costin Dobrin, Jacob G. Naimark, Edward R. Cook, Benjamin I. Cook, Richard Seager, Mark A. Cane, and Serena R. Scholz, “A Quantitative Hydroclimatic Context for the European Great Famine of 1315–1317,” Communications Earth & Environment 1, no. 1 (2020): 3.

- Baek, et al., “A Quantitative Hydroclimatic Context,”2.

- William Chester Jordan, The Great Famine Northern Europe in the Early Fourteenth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 32.

- Sharon DeWitte, and Philip Slavin, “Between Famine and Death: England on the Eve of the Black Death—Evidence from Paleoepidemiology and Manorial Accounts,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 44, no. 1 (2013): 38.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 9.

- Jordan, The Great Famine: Northern Europe, 32.

- Henry S. Lucas, “The Great European Famine of 1315, 1316, and 1317,” Speculum 5, no. 4 (1930): 346.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 9.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 10.

- Ibid, 18.

- Jordan, The Great Famine: Northern Europe, 31.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 18.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- John de Trokelowe, and Henry de Blaneforde, Johannis De Trokelowe Et Henrici De Blaneforde Chronica Et Annales: AD 1259–1296, 1307–1324, 1392–1406, ed. Henry Thomas Riley, trans John Aberth (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 94.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 35.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Campbell, The Great Transition, 212-3.

- Ibid, 398.

- Ibid.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 34.

- Campbell, The Great Transition, 398.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 34.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 19.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 21.

- Ibid, 19-20.

- Campbell, The Great Transition, 215.

- Ibid, 398.

- Ibid, 215.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 34.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ian Kershaw, “The Great Famine and Agrarian Crisis in England 1315-1322” Past & Present 59, no. 1 (1973): 9-10.

- Kershaw, “The Great Famine and Agrarian Crisis in England 1315-1322,” 9.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 28.

- Ibid, 34.

- Ibid, 24.

- Ibid, 23.

- Ibid, 39.

- Campbell, The Great Transition, 176.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 23.

- Campbell, The Great Transition, 192.

- Ibid, 211.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 28.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Campbell, The Great Transition, 211.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 209-211.

- Ibid, 213.

- Ibid, 215.

- Ibid, 213-215.

- Ibid, 221.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 222.

- Ibid, 192.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 166.

- Kershaw, “The Great Famine and Agrarian Crisis in England 1315-1322,” 59.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 17.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 15.

- Margaret L King, A Short History of the Renaissance in Europe (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017), 67.

- King, A Short History of the Renaissance in Europe, 67.

- Ibid.

- Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, 41.

- Ibid, 39.

- Queen Mary Master. August. 1320. Manuscript, 275 x 175 (mm). In The Queen Mary Psalter. (Introduction Page image)

- Weimar Biblia Pauperum/Apocalypse. 1340. Manuscript, 480 x 300 (mm). Erfurt, Germany. (Main Menu image)

- Lufft, Hans. The Wittenberg Bible: The Plague of the Boils. 1572. Book, 115 x 152 (mm). London: British Museum. (Overview image)

- Master of the London Wavrin. Recueil des Croniques et Anciennes Istoires de la Grant Bretaigne. 1471. Manuscript, 450 x 340 (mm). London: British Library. Accessed from https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?IllID=40018&Size=mid. (Effects of Crop Failure image)

- Forman, Sir Robert. Forman Amorial: Robert the Bruce. 1562. Manuscript. Edinburgh: British Museum Harleian. (War with Scotland Image)

- Londoners Fleeing the Plague are Barred by Country Dwellers. 1625. Illustration. New York: Public Library. (England image)

- Penni, Luca. Series: Histoire d’Apollon et de Diane. 1547. Print, 80 x 107 (mm). London: British Museum. (Scotland image)

- Cannibalism in Lithuania. 1571. Painting. Accessed fromhttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cannibalism_1571.PNG (Ireland image)

- Il Trionfo della Morte. 1446. Fresco, 6 x 6.42 (m). Palermo: Palazzo Abatellis. (Social Impact image)